<< Learning Center

Media Accessibility Information, Guidelines and Research

In Education, Transition, and Life: Teachers Made the Difference

By Ernest E. Hairston

As they spend each day "just doing their jobs" in the classroom, teachers influence their students in profound and far-reaching ways. As I look back, I see two teachers who shaped my upbringing, my education, and finally, my lifelong career. William King, the first teacher I had who was black and deaf, was my role model. After graduating from West Virginia State College in Institute, WV, he taught nearby at the West Virginia School for the Colored Deaf and Blind (WVSCDB) which I attended.

King taught me to appreciate poetry. Other teachers in reading and literature reinforced that appreciation by encouraging us to memorize and recite poems as part of the reading and rigidly taught grammar, but it was primarily King who enabled me to persist with the grammar lessons and enjoy my reading—activities that I believe shaped my literacy skills.

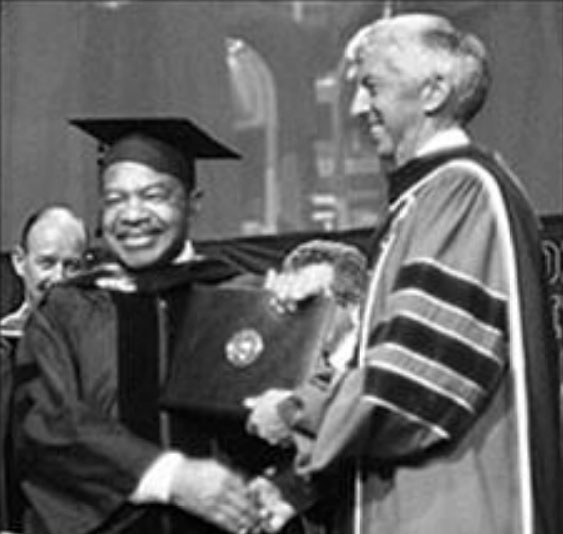

But perhaps the most influential teacher in my life was Malcolm Norwood. (See Fig. 1) Norwood, a white deaf man, entered my educational picture when the U.S. Supreme Court decided that the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, the separate-but-equal doctrine that had existed in our country, was unconstitutional. As a result, my classmates at WVSCDB and I were integrated with the white students at the West Virginia School for the Deaf and Blind (WVSDB) in Romney, where Norwood was a supervising teacher.

Because of my high score on the standard test administered to students at WVSDB, I was placed in a college preparatory class with two other students—Paul Adams, originally from my own school, and Rita Burgess who had always been a Romney student. Norwood became our English teacher, but he was more than that. He was also, in a time before the word was often used, a mentor.

In our senior year, all three of us took the Gallaudet entrance examination and passed it. Graduation was approaching when "Mr. Norwood" asked me what I planned to do after I had my diploma. At WVSCDB I had trained in barbering, tailoring, and dry cleaning. I knew a few deaf barbers. As independent businessmen, they made good money, drove nice cars, and dressed decently. So I had an answer ready and responded immediately.

"Be a barber," I said.

Barbering wasn't good enough for Norwood.

He told me to go to college.

How Teachers Help Make History

I was startled. There was only one college for deaf students in the United States—Gallaudet College in Washington, D.C. Only one black deaf individual—Dorothy Lapsley, who also graduated from WVSDB and worked as a beautician—I knew had ever attended there.

But Norwood was adamant. I should go to Gallaudet, he said.

I thought, "Why not?"

Five years later, I graduated from Gallaudet with a degree in education. I taught at various places. I received my master's degree in administration and supervision from California State University, Northridge, and directed a federally-funded rehabilitation facility.

The Connection Continues: On the Job

But my connection to Mac Norwood was far from over. When a position as education program specialist with the U.S. Office of Education's Bureau of Education for the Handicapped (now Office of Special Education Programs) became available, it was Mac Norwood, assistant chief and later chief of the Captioned Films and Media Services Branch (later called Captioning and Adaptation Branch) who recommended me for the job and hired me.

As we worked together on the federal level, I watched as the colleague I called "Mac" continued to advance both personally and professionally. When Mac received his doctorate from the University of Maryland, he noted that the Ph.D. would not earn him a promotion or an increase in pay, but when others would argue with him and say, "I have a Ph.D.," he could reply, "So do I."

I thought that was cool and began to pursue my doctorate as well.

In 1994, I received my Ph.D. in special education administration.

Mac remained my supervisor and mentor for approximately 16 years. When he retired, I, of course, applied for the position. After a nationwide search, I was offered the position of chief, Captioning and Adaptation Branch. I have since been promoted to associate division director/team leader for the National Initiatives Team within the Office of Special Education Program's Research to Practice Division with increased staff and responsibilities.

Occasionally, I have the great pleasure to be visited by my own former students. As a former teacher, I am pleased to be approached by these young adults who tell me how I have "helped" them or "influenced" them—when I thought I was just doing my job.

Yet my own life took the turns it did because of the powerful impact of two teachers. Barbering may be lucrative and challenging. It made a great series of part-time and summer jobs as I made my way through school! I am pleased, however, with the skills that I was able to develop and decisions I was able to make because of William King and Mac Norwood, two men who were my teachers.

Whether the issue is reading, mathematics, or transition, my own life shows that although it may not be evident in the day-to-day interaction in the classroom, teaching is a lot more than just doing a job.

About the Author

Ernest E. Hairston, Ph.D., was education research analyst within the National Initiatives Team within the Office of Special Education Program's Research to Practice Division at the U.S. Department of Education, in Washington, DC. He was also a DCMP project officer and a former teacher. He coauthored Black and Deaf in America: Are We That Different.

Tags:

Please take a moment to rate this Learning Center resource by answering three short questions.