<< Learning Center

Media Accessibility Information, Guidelines and Research

Blindness and Black History: One Leader's Perspective

By Freddie Peaco

Preserving a History

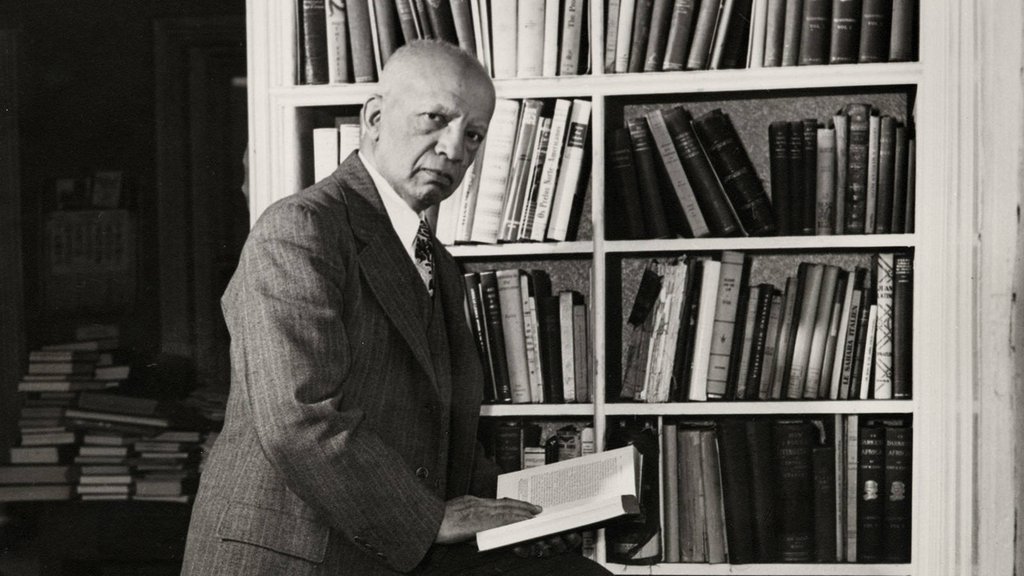

When Carter G. Woodson created the observance of "Negro History Week," which later became "Black History Month," he inspired African Americans to protect and uphold their history, which not only includes written history, but also oral history and the preservation of special and unique artifacts. Our history is our genesis, our present, and our path to the future. It explains how we came to be, who we are, where we are today, and where we are going tomorrow.

Woodson believed that Blacks should know their past in order to participate intelligently in the affairs in our country. He also believed that Black history is a firm foundation for young Black Americans to build on in order to become productive citizens of our society.

The countless contributions of African-American men and women to the advancement of civilization vary widely and are numerous. Unfortunately they have long been minimized, overlooked, and suppressed by many people, but Black History Month helps us preserve and celebrate this rich, diverse legacy, which is saturated in those contributions.

United by Peace

One group of people who greatly enhance and strengthen that diversity is African Americans who are blind or visually impaired. They have uniquely contributed in a wide variety of cultural, historical, and societal applications. Personally, my blindness and being an African American motivated me to try harder, strengthening my desire to excel and accomplish what others told me I could not do, such as achieve academic success and independence and be productive.

While I strongly believe that African Americans are Americans first, it is still essential that we have a record or knowledge of what generations before us have accomplished. I long for a multiracial nation united by peace and tolerance of each other. But as with other ethnic groups, we have our culture and should be proud of it, and other Americans should also understand it. This sharing and understanding can lead to self-reliance and racial respect.

Sharing and understanding also help dispel myths and stereotypes that have all too often plagued this community. This is where I find a strong parallel between my experiences as a blind African American and the experiences of my sighted African-American peers. In both instances there are myths and stereotypes surrounding our contributions and abilities. Even though these misconceptions often come from a small kernel of truth, we must make every effort to learn our history in order to better ourselves.

Resources and Accessibility

However, resources for obtaining current and accurate information are not readily available to people who are blind. Despite good intentions, many school districts, including schools for the blind and schools for the deaf, around the country simply do not have the body of knowledge or resources needed to adequately educate blind and visually impaired children. I believe the Described and Captioned Media Program (DCMP) can make a lasting contribution to your library of accessible materials on Black history. I emphasize accessible materials because equal access is dreadfully lacking for students with vision loss. Sometimes we get small bits and pieces of information when materials are not accessible, but having this material in an accessible format has given a profound sense of dignity to all Black Americans and the opportunity for those with vision loss to learn, make choices, and interpret facts.

DCMP is the largest collecton of described educational media."

The Described and Captioned Media Program is the largest free-loan library of described educational media. This is the kind of accessible information that will inspire students' confidence, enhance their self-esteem, and improve their attitude, all of which breed success in students who all too often have been underestimated and overprotected.

The DCMP media items in the library collection are captioned for the deaf and described for the blind, and this material is freely distributed to schools across the nation. The DCMP expends the time and resources to include materials related to Black history and culture and make them available to teachers and parents at no cost. I am a staunch supporter of description myself, which provides immeasurable assistance in making films, movies, plays, etc. more meaningful and understandable.

This service can greatly enhance the participation of people with vision loss in the observance and celebration of Black History Month by arming them with access to information, inspiration, and knowledge. As the DCMP has content for your use on the topic of Black History Month, remember that teaching about African-American culture not only benefits students for a month, but will reach generations and last a lifetime.

A Lifetime of Experience

I retired from the Library of Congress, National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (NLS) in July 2009 after 42 years of service with the federal government. While at the library I held several positions, primarily in the reference section.

I coordinated the production of two publications and produced other reference publications as needed. I also served as liaison with other federal agencies to identify and encourage the production of their documents in accessible formats.

I represented the Library at conferences and meetings, conducted workshops and staff national exhibits around the country, and coordinated and conducted tours of NLS.

In addition to my employment I have been involved with several organizations/activities.

Some of them include:

- DC Council of the Blind

- Association for Education and Rehabilitation of the Blind and Visually Impaired (AER)

- National Braille Association (NBA)

- Board of Directors, the Lighthouse, Inc.

- Board of Trustees, Metropolitan Washington Ear

- Friends Group of the District of Columbia Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped

I started from very meager beginnings. I was born in North Carolina in the 1940s, and when a visual impairment was discovered around age six or seven, I attended the Governor Morehead School for the Blind in Raleigh. After graduation I came to Washington, D.C. in 1961 to attend Howard University where I earned a bachelor's degree and a master's degree from American University.

I continue to seek training in the use of various types of assistive technology.

Participation in the church and the community are also very important to me. I am a member of Northeastern Presbyterian Church in Washington, D.C. and am active in many organizations. I am an ordained elder and serve on several committees, including Northeastern Presbyterian Women and the Evangelism & Outreach committee.

My husband and I have a grown son and two granddaughters.

Conclusion

The aforementioned accomplishments may seem ordinary for the average employed sighted person. Unfortunately, most sighted people, including professionals, have very low expectations for a blind person, and this unfortunate fact can be paralleled to the goals for Black History Month observances that take place around this great nation. Through knowing and understanding our history, we can work to dispel myths and stereotypes associated with race and disability.

I relay this information to both introduce myself and to demonstrate my perception of Black History Month as a special opportunity for reflection, to encourage and motivate others to succeed, and to emphasize self-reliance and respect.

And so we combine all of these contributions, the struggles, the achievements and accomplishments, the myriad experiences, and that rich legacy we hold so dear and allow these to be our motivation to work together to ensure our history is accurately recorded and available for all who come after us, so that they, too, will know about, appreciate, learn from, and continue to treasure and celebrate it. And this starts with access.

Tags:

Please take a moment to rate this Learning Center resource by answering three short questions.